Africa: When successors rebelled against their mentors

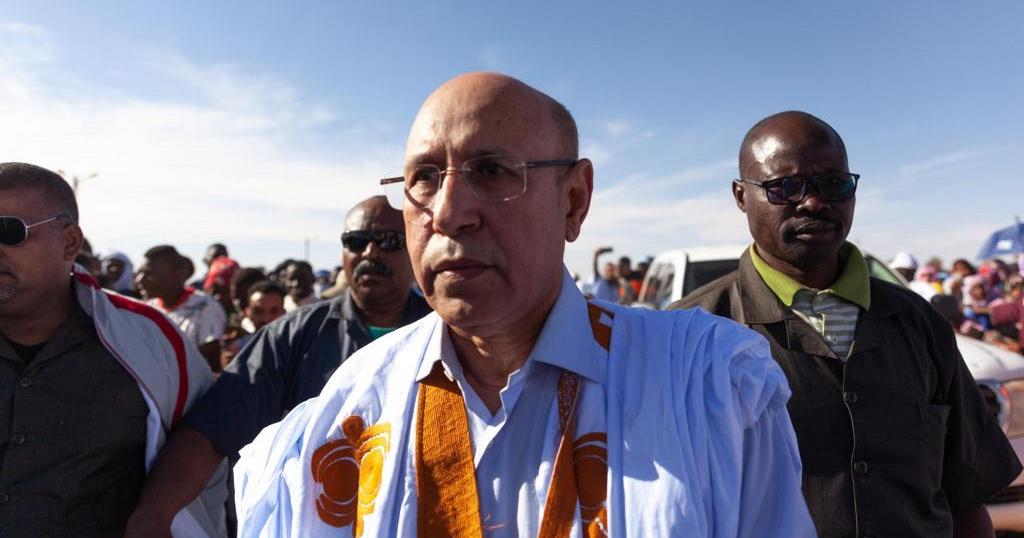

Mauritania’s former president Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz has become the latest leader on the African continent to fall out with his ‘anointed’ successor, over control of the ruling party.

On the African continent, it is not uncommon to have leaders that rule their nations for decades, and when they eventually bow out, their prefered successor usually sails to power.

It is widely expected that these successors would protect the interests of their mentors and continue the agenda, developmental or not, pursued by the predecessors.

This strategy has been effectively used by liberation movements that became ruling parties after independence in Southern Africa, including Tanzania, Namibia and Mozambique among others.

It does not however always go according to plan as Mauritania’s Aziz, Angola’s Eduardo dos Santos and Botswana’s Seretse Ian Khama found out.

Mauritania’s Aziz is frustrated

In less than six months since Mauritanian President Mohamed Ould Cheikh El Ghazouani was elected, he has moved to consolidate his grip on power, and in the process sideline his predecessor and one-time mentor.

Early in 2019, suspicions ran high that Aziz, who came to power in a bloodless coup in 2008, wanted to breach the constitution and run for a third term. Instead, the former general backed his loyal aide and defence minister, Ghazouani.

Ghazouani’s victory at the polls in June became little more than a formality once he had enough support nationwide from the Union for the Republic (UPR), a party founded by Aziz in 2009, who won his first five-year term that year.

Before the vote, Aziz signalled he would not quit politics and intended to retain his control of the UPR.

But Ghazouani’s cool assertion of authority came as a bitter shock to his predecessor, who long muzzled the opposition and ruled for a decade, accustomed to loyalty, honours and glory.

The new leader dismissed the heads of the presidential guard appointed by Aziz and last weekend won the outright backing of the UPR during its party congress in Nouakchott, which notably was not attended by its founder. Some 2,250 party delegates elected a new National Council without opposition.

“This is a time of consensus around our President Ghazouani, who has convinced everybody, including the opposition. Nobody speaks any more of the other (Aziz), except on social media.

He should go into retirement,” UPR member Ahmed Ould Salem told AFP during the congress, despite long standing support for the former president.

On Saturday, the UPR admitted four new parties into its coalition, including Adil, an opposition movement whose two members of parliament will strengthen the large majority the UPR enjoys in the chamber.

The new head of state has also won over Sidi Mohamed Ould Boubacar, a former prime minister who came third in last year’s presidential election.

Clearly feeling his own party slip from his grasp, Aziz held a press conference where he denounced “undermining, unconstitutional action, in total illegality, on the part of people who are not even members of the party, by the order of the authorities.”

He also raised the possibility of founding a new party, but the official media did not attend the briefing.

But fresh elections are along way off, with parliamentary, regional and district polls in 2023, and the next presidential race not until in 2024.

Tough times for the Dos Santos in Angola

Jose Eduardo dos Santos ruled Angola for 38 years, a time widely associated with corruption and nepotism.

His chosen successor, and defence minister at the time, Joao Lourenco became president in 2017. Since taking over, Lourenco’s government has embarked on a relentless campaign to root out corruption and recover funds embezzled from the state coffers.

Lourenco’s anti-corruption campaign placed him on a collision course with the dos Santos family, and many members of this powerful household have fled the country, citing death threats.

The former president’s daughter, Isabel dos Santos is under investigation for alleged irregularities involving state companies including the OPEC nation’s giant state oil company Sonangol. Authorities froze her bank accounts this week.

Isabel, who is commonly refereed to as Africa’s wealthiest woman, was appointed head of Sonangol in 2016 but was forced out the following year, in one of the first acts undertaken by Lourenco to remove dos Santos relatives from power.

The former president’s son, Jose Filomeno dos Santos, 41, who is Isabel dos Santos’s half-brother, went on trial in early December for alleged corruption. He is accused of embezzling as much as $1.5 billion from Angola’s sovereign wealth fund during his 2013-2018 stewardship.

In September last year, the former president quit his post as ruling party chairman, and has denied Lourenco’s allegations that the state coffers were emptied by the previous administration.

Botswana’s angry Khama

In Botswana, the former president Ian Khama respected the ruling Botswana Peoples Party, BDP, tradition of handing over power to his successor Eric Masisi a year to the 2019 general elections.

Khama however, clashed with Masisi months after stepping down over certain policy positions, and ultimately backed opposition candidates in last year’s national elections.

“The person I appointed to replace me was, as soon as he came to power, very autocratic, very intolerant, and this led to a decline in democracy,” he said.

“When he was my vice-president (…), he never showed off the problems we see now.’‘

The ex-president last month threatened to sue the government for defamation after the state anti-graft agency cited him and some of his allies as being part of a syndicate that swindled billions of state funds.

The post Africa: When successors rebelled against their mentors appeared first on Nile Post.

0 Response to "Africa: When successors rebelled against their mentors"

Post a Comment